Runa Hestad Jenssen explores how the arts and listening challenge assumptions and invite belonging through education. In this article, published in the British Educational Research Association (BERA) magazine, she describes a conversation with Kristie Mortimer, New Zealand dance educator and postdoctoral researcher at Nord University.

BERA undertakes educational research in the UK. Its magazine, Research Intelligence, reaches 3000 members across 60 countries.

BERA undertakes educational research in the UK. Its magazine, Research Intelligence, reaches 3000 members across 60 countries.

The autumn issue of the magazine has a special focus on education in prisons. Runa’s article is reproduced below.

I visited a prison for the first time in May 2024. The experience still sits in my body. The heavy-handed search at the gate. The curt “You’re fine. Move on.” And then – unexpectedly – warmth. Smiles and hugs in the chapel, despite the “no touching” signs. A choir entered. Men and women sang together. Between songs, they shared stories.

One man said he hadn’t seen so many women at once for 15 years. Another said, simply, “When I sing, I live.” I watched them – singing bodies, living voices. I saw friendship, community, a belonging many had never known. On the way out, they sang “The Old Triangle”. Even now, I can still hear them – voices resonating far beyond the prison walls.

What does it mean to teach voice if some voices are silenced behind walls? If music education is about connection, about making space for every voice – especially those the world tries to keep out – how do we listen?

Later, at my kitchen table, I told my mother, a retired teacher, about the visit. I shared everything – the choir, the emotions, the questions I was still turning over. She listened, then said, almost offhandedly, “I taught in prisons for years.”

I stared at her. “You what? How did you do that?”

“Like I normally do,” she said, smiling.

It took me a moment to understand. I had imagined prison education as something extraordinary, something that required special methods or courage. She saw it differently: just teaching. Students who needed education. Going where they were.

She added, “Don’t you remember? I brought you on those trips.” I blinked, and then I did remember – sitting in cafés with my homework, waiting for her. I had no idea. I thought she was “only teaching”. And well – she was.

Understanding voice in education

That moment changed how I understood voice in education. It’s not about heroic acts or unusual interventions. It’s about presence. Showing up. Meeting others as they are, where they are.

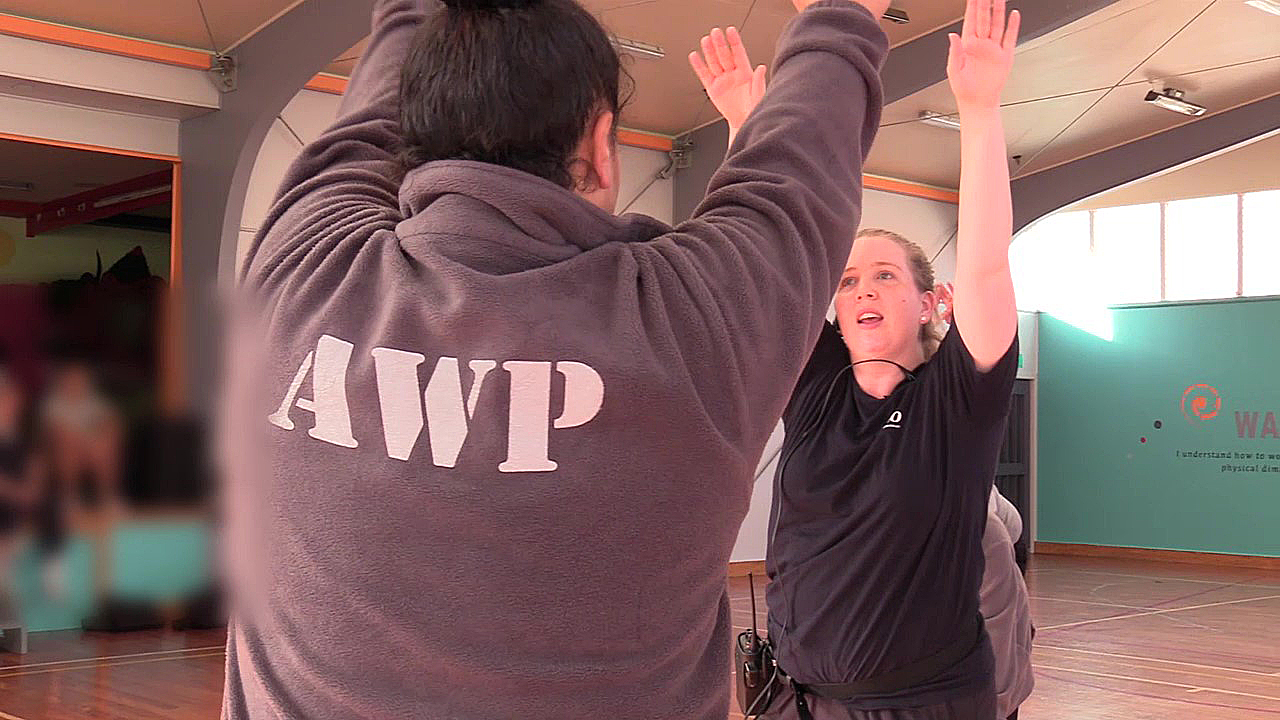

A similar clarity emerged when I spoke to a dance educator, Kristie Mortimer, about her work in a men’s prison in Aotearoa New Zealand. She said she started cautiously, calling her sessions “movement workshops” rather than “dance”, worried the word might deter participants.

A similar clarity emerged when I spoke to a dance educator, Kristie Mortimer, about her work in a men’s prison in Aotearoa New Zealand. She said she started cautiously, calling her sessions “movement workshops” rather than “dance”, worried the word might deter participants.

Slowly, trust grew. She invited the men to create movements for each syllable of their names. At first, there was hesitation – even withdrawal. But then came laughter, rhythm, pride. Connection.

The men reflected on the experience with words like “different” and “out of our comfort zone”. But it was different in a way that felt real – alive.

These moments remind me of what philosopher Sara Ahmed (2016) calls “epistemic discomfort”, the idea that feeling uncertain or displaced can be a source of learning. Claire Hemmings (2012) builds on this: “To know differently, we need to feel differently.”

It’s not the “othered” who need transformation. It’s often the majority who need to feel – and listen – differently.

Music, education and prisons

As I wrote about all this, music filled our home. My husband rehearsed with his folk trio. Our children lingered nearby, wrapped in the sound. I was in the middle of writing about prisons and music when the pianist asked, “What’s it about, Runa? You seem deep in thought.”

“Music, education and prisons,” I said.

He shrugged. “Oh. I play in prisons every week.” My fingers paused over the keyboard. “You what?”

“It’s part of my work with the Church City Mission,” he said. My husband nodded too. “Remember when we played in Hamar prison?”

I looked at them both. This, too, was part of their work. Just music. Just teaching.

These repeated recognitions – in my family, in research, in education – have taught me something. The threshold isn’t just a border between inside and outside. It’s a meeting place. A space where we might listen to voices that challenge our assumptions. A space where belonging is possible, even if fleeting.

Hope lives here too. As Rebecca Solnit (2010) writes: “To hope is to gamble.” To pause, to imagine, to make space for another’s voice – that is a kind of wager. But it’s also where transformation begins.

Making education more inclusive and socially just

We often ask what we can do to make education more inclusive, more socially just. But maybe the question is not what to do differently, but how to be differently. How to listen. How to show up. How to meet others with authenticity and care.

Maybe it is not about doing something “special’ for those who are othered. Maybe it is about being authentic, real and very pragmatic – enabling people who, in so many ways, have felt othered to finally feel seen and heard.

Like the singing voices resonating far beyond the prison walls.

The threshold isn’t in or out. It’s a space where voices can meet each other and be heard, despite their differences.

Maybe it’s not about special programmes or big gestures. Maybe it’s about a quiet truth my mother knew all along.

Only teaching.

References

Ahmed, S. (2016). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press.

Hemmings, C. (2012). Affective solidarity: Feminist reflexivity and political transformation. Feminist Theory, 13(2), 147–161.

Solnit, R. (2010). Hope in the dark: Untold histories, wild possibilities. Canongate.