Painting that rehabilitates: new insights at Auckland Prison

20 June 2011

There is much to be said about the benefits of art-making in any community of artists. However, the self-taught art skills and practice of prisoner Rawiri (not his real name) at Auckland Prison offers new insights into the rehabilitative value of the arts in prisons.

In October 2010, and again in May 2011, Arts Access Aotearoa attended InsideOut exhibitions of prison art at Mairangi Arts Centre on Auckland’s North Shore. Many of the works displayed in the exhibitions were made by artists who over time have developed an art practice. Rawiri had a number of works in the exhibitions.

In October 2010, and again in May 2011, Arts Access Aotearoa attended InsideOut exhibitions of prison art at Mairangi Arts Centre on Auckland’s North Shore. Many of the works displayed in the exhibitions were made by artists who over time have developed an art practice. Rawiri had a number of works in the exhibitions.

With the assistance of Mark Lynds, Manager Contracts and Services, Department of Corrections, Arts Access Aotearoa’s Prison Arts Advisor, Moana Tipa, was able to have a telephone conversation with Rawiri about his art practice.

“It’s his passion for painting – building his technique, and working with colour and light – that has activated a stream of thinking based in his ancestry, his whakapapa Māori,” Moana says.

“It’s this deeper reconciling outcome of art-making that is the goal of many artists, whether incarcerated or free.”

When Rawiri was young – seven or eight-years-old – he had an “on-and-off-again” relationship with art-making. “I started to draw with pencil and crayon. Then when I was about nine or ten I realised, ‘Wow! I can draw’. I got into art again at intermediate and won an art award at high school. I was good at it.”

Rawiri’s reconnection with art-making happened inside the prison walls, he says. “I started back in 2003 and got into pencil work hard out for three years. Then I worked with colour pencils for one-and-a-half years. But I wanted more from my images. I wasn’t making the outstanding thing I was looking for.”

Rawiri’s reconnection with art-making happened inside the prison walls, he says. “I started back in 2003 and got into pencil work hard out for three years. Then I worked with colour pencils for one-and-a-half years. But I wanted more from my images. I wasn’t making the outstanding thing I was looking for.”

In 2007, he started painting without much idea of what he needed to know. So when he met Auckland artist and prison art tutor, Robyn Hughes, “korero with her was all about colour”.

“I pushed myself because I wanted to see how far I could go towards a higher standard. I took the challenge on and I did a lot of portraiture. But it didn’t work for me.”

Looking for links to himself

He needed to make work that he had an interest in or some relationship with; something that was close to or a part of him. Making commissions for others was useful from time to time but that work didn’t provide the link to himself that he was looking for.

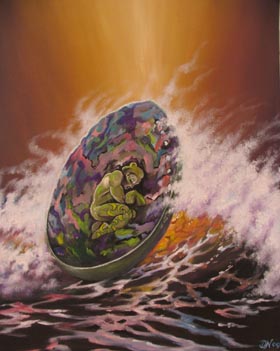

That changed radically once the painting process began. “The more I painted, the more I began to see that colour linked with my thoughts and ideas,” Rawiri says.

As he continued to experiment, use and “push” his concepts of colour, aspects of tikanga – his own Māori world – began to emerge.

As he continued to experiment, use and “push” his concepts of colour, aspects of tikanga – his own Māori world – began to emerge.

“Painting has been a big door opener for me,” he says. “It helps me get to my ideas. I have that whole world of oranges, reds, yellows and blues that gives me heaps to work with.

“Working with colour is a skill I’ve built and developed. Like a tradesman learns a trade, I work with colour. When I took the art thing up four years ago – really seriously, day and night – it was a total focus to get my skills up. I knew I could build enough skill over those years through trial and error, and through reading.

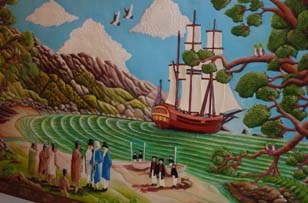

“Now I have those skills to work with, I can respond to the ideas of tikanga Māori, the past and the future that will come. My work has become real. It is part of me and what I know. I base my work in New Zealand history – to the links of the past and the future.”